LIMEX HELPDESK

Contact LIMEX for free advice:

Need FREE advice?

Talk to the LimeX team

Wed 29 January 2025

Clubroot is one of the most destructive diseases of brassica crops, such as cabbages, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cauliflower and oilseed rape, both globally and in the UK. It’s caused by Plasmodiophora brassicae, a soil-borne slime mould fungus.

The fungus has a complex life cycle. It’s an obligate parasite, requiring a host to complete its life cycle and create more spores. But those spores are so well-protected by tough cell walls that they can survive dormant in soils for up to 20 years,

The classic clubroot infection symptoms are white-coloured abnormal growths or galls on roots. These galls disrupt the plant’s ability to take up nutrients and water, leading to above-ground stunting, yellowing and wilting of plants, and ultimately reduced yields.

Resting spores are released back into the soil when the galls decompose after the crop matures, so the infection can start again.

Clubroot is first seen in patches in the field, often associated with areas of poor drainage and aeration, resulting in anaerobic conditions. The disease is encouraged by temperatures of greater than 15C, high soil moisture and acidic soils (< pH 6.8)

A potential pathogen for every species of brassica crop, P. brassicae also infects cruciferous weeds, such as shepherd’s purse and charlock, and has even been found in the roots of non-cruciferous plants, such as grasses. However, it does not cause galls in such non-hosts.

The wide host range and extended survival of spores means clubroot is challenging to manage once established.

There is no single method to eliminate clubroot, so an integrated approach that combines several management techniques is essential for control.

1) Practice effective on-farm hygiene

Clubroot is spread by moving contaminated soil containing resting spores from one area to another. Following good on-farm hygiene practices can help in reducing spread. Where working in an infested field at a minimum, SRUC advises:

2) Longer rotations and weed control

Some research has shown that clubroot has a half-life of four years and is undetectable after 17 years, while other reports claim that resting spores can last for 20 years or more.

What is not in doubt is that continuous production of brassicas in infested fields will cause the multiplication of inoculum via spore release. Best practice suggests that rotations between brassica crops should be at least four to five years. That might not be practical in field brassicas, but three years should be considered the minimum.

Cereals, peas, and beans are good break crops, but grass might not be because of the evidence that pathogens can infect and survive in the roots without galling.

With cruciferous weeds, such as shepherd’s purse and charlock, acting as a host for clubroot, control of these weeds prevents the release of spores into the soil. Neglecting weed control can negate the benefits of other control measures, such as liming.

3) Soil pH and calcium management with LimeX

Lime application is the traditional method for managing clubroot, especially with mild to moderate levels. It raises soil pH and increases the amount of calcium in the soil—both are essential for control. Raising pH without raising calcium or vice versa is not as effective.

Studies show neutral or slightly alkaline soils that are free-draining and well-aerated limit infections. In contrast, independent of this, highly available calcium levels in the soil play an active role in limiting the germination of spores.

Raising soil pH and increasing the amount of available calcium in the soil make the choice of lime product critical.

The fine particle size of LimeX, where every particle is smaller than 150 microns (0.015mm), allows for rapid breakdown and release of calcium into the soil while raising pH rapidly. LimeX begins to work within 4-6 weeks of application, compared with traditional agricultural lime, which can take up to six months to have an effect.

This rapid reactivity is critical to controlling clubroot, especially when growers work with short crop rotations or higher disease pressure. Applications should be made pre-planting and incorporated into the seedbed to achieve a calcium and pH burst early in the crop’s life.

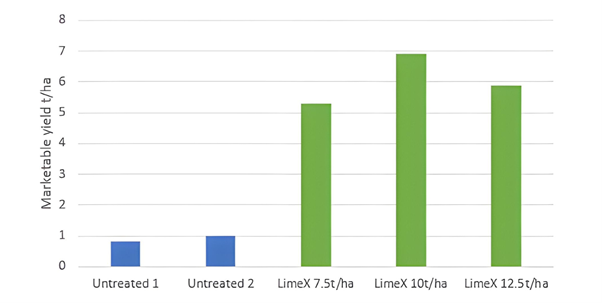

Trials conducted by Dr Roy Kennedy from Warwick College University Centre in calabrese back in 2009 (Figure 1) showed a marketable yield of 6.9t/ha from applying 10t/ha of LimeX in a high-pressure situation compared with just 0.9t/ha from the untreated.

Figure 1. Warwick College and University Centre 2009, the effect of LimeX on marketable yield of calabrese in a high-pressure clubroot situation.

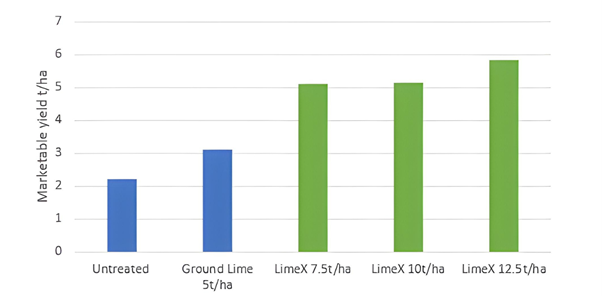

A second trial in 2010 (Figure 2) showed a smaller but still significant increase of around 2.9t/ha in marketable yield. That compared with just a 0.9t/ha marketable yield increase from applying 5t/ha of ground lime.

Figure 2. Warwick College and University Centre 2010, the effect of different liming materials on marketable yield of calabrese in a high-pressure clubroot situation.

Given that those results were so conclusive, we didn’t feel the need to rerun the trials. LimeX now plays a vital role in controlling clubroot in farms across the UK, particularly ahead of high value veg brassicas.

4) Resistant cultivars

Resistant varieties offer a potentially valuable tool for managing clubroot. As the genetic basis of clubroot resistance becomes more studied, resistant varieties may become more widely used. Their use, however, is complicated by the presence of several different races of P. brassicae.

Over-reliance on resistant cultivars is another potential danger, as it can lead to the resistance being overcome. That was shown with Mendel clubroot resistance in oilseed rape, providing good reasons why varietal resistance should be used in conjunction with other management strategies.

5) Biological and Chemical control

Very few chemicals have consistently controlled clubroot, and those that were more effective, such as mercury chloride, have long since been removed from the market.

Some biological products, such as Bacillus subtilis, have shown some efficacy in trials against clubroot in canola, but it is not widely used.

Written By Glenn Carlisle

Thu 4 September 2025

Over 50% of arable soils are below the target pH of 6.7 recommended in...